DORA - Regulation of Technologies in the Financial Sector

Key Facts

- With the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), the EU wants to make the financial sector more resilient against IT disruptions and cyber attacks

- DORA is available in draft form, trialogue procedure not yet completed, entry into force probably not this year

- DORA will harmonies existing requirements for risk management of modern technologies across the EU

- Third-party ICT providers, such as hyperscalers or core banking providers, will in future be audited in the same way as banks and insurance companies, which have been subject to supervision to date

- Hyperscalers will be centrally audited by ESA and national supervisors and pay for supervisory activities

- DORA will require more STEM expertise in the management and thus also supervisory bodies

- Certifiable information security management systems (ISMS) will become EU best practice in the financial sector

- Increased administrative burden in the future due to new reporting requirements and approval procedures

- Financial companies declared as critical will have to prove their digital operational stability on a regular basis through threat-oriented penetration tests

- Establish hybrid IT auditing as the standard for manual-automated audit procedures

Introduction

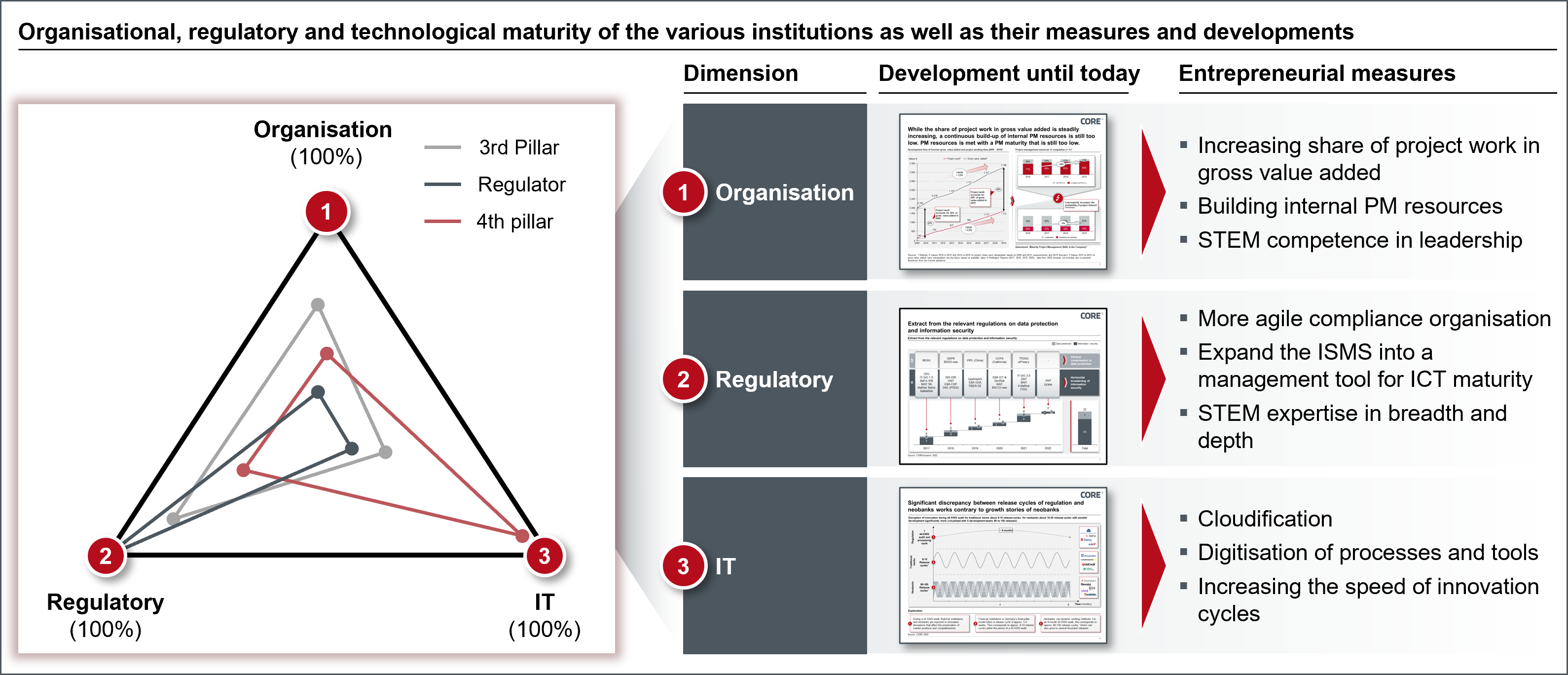

The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) creates an EU legal framework "on the operational resilience of digital systems in the financial sector". Basically, DORA combines existing regulations on security measures, reporting and verification of licences, but expands and deepens them in selected places. Third-party ICT providers are included, giving the so-called lead supervisor (EBA, ESMA or EIOPA, depending on the type of supervisory object) the necessary means to enforce standards in financial market stability through intervention options such as penalty payments. As a comprehensive set of rules for information security, DORA will have a comparable impact in the three dimensions of organization, regulation, and IT in financial companies as the GDPR has had on the protection of personal data since it came into force in May 2018. While the GDPR applies to the entire economy and administration, but only addresses the protection of personal data, DORA will "only" apply to all financial companies - this also includes various administrative entities, but DORA aims to protect all information, including personal data. Figure 1 illustrates the framework in the three dimensions of organization, regulation and IT for the three entities insurance, regulator and neo bank.

Figure 1: DORA intervenes in an organisation's maturity level in the three dimensions of organisation, regulation and IT

Although the European regulations with rules on ICT security and reporting in the financial sector such as the NIS Directive, GDPR, PSD 2 including various RTS (Regulatory Technical Standards) apply in every member state of the European Economic Area, many countries, including Germany, interpret these requirements nationally. In Germany, the financial sector must fulfil legal requirements relating to information security and risk management from MaRisk , XAIT (BAIT / KAIT / VAIT / ZAIT ), GeschGehG , FISG and IT-SiG 2.0 (see Figure 1). This "multiple regulation" of the same ICT in different sets of regulations provokes inefficiencies and even ineffectiveness due to overlaps, inconsistencies and multiple requirements for the security of ICT.

The intention seems to be that DORA should harmonies European and national regulations and potentially make them obsolete. It remains to be seen whether the member states will forego their own regulations, as administrative structures rarely give up power structures once they have been achieved without resistance. This is where DORA comes in and makes it easier for cross-border financial companies to do business internationally through comparable regulations and the EU-wide recognition of audits. Therefore, the DORA draft is to be supported from the perspective of further European integration as well as increasing the competitiveness of the participants in the European financial market.

Figure 1: DORA intervenes in an organisation's maturity level in the three dimensions of organisation, regulation and IT

In the following, the content of the DORA is presented in detail. Challenges for the financial sector from the authors' point of view are outlined. Following this, information on how to achieve compliance with DORA is outlined.

DORA subsumes requirements for security in the financial sector, expands the circle of objects of supervision and imposes new and higher requirements in individual areas of security.

Contents of DORA

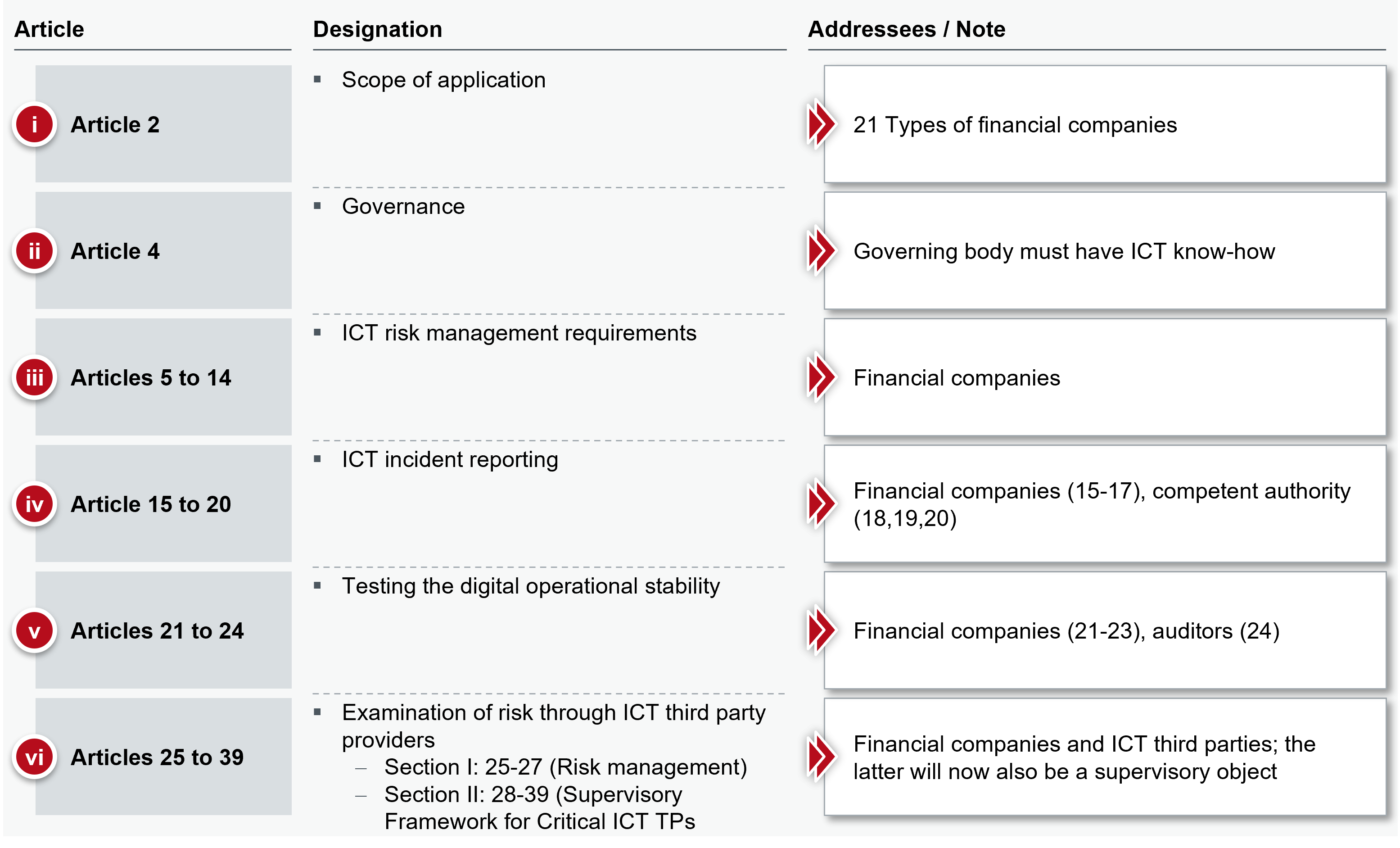

While the three article blocks "Requirements for ICT risk management", "Reporting of ICT incidents" and "Audit of digital operational stability" address financial companies and thus also ICT third-party providers, the article block "Audit of risk by ICT third-party providers" regulates only technology providers. With 15 articles, the requirements for third-party ICT providers such as hyperscalers are formulated in detail. Functional providers for core banking system solutions are also included in the scope.

Scope of application (Article 2)

The DORA expands the regulatory framework from the "classic" regulatory objects of credit institutions, payment institutions, e-money institutions and investment firms to a total of 21 different types of financial companies. The new regulatory object "ICT third-party providers" is particularly significant.

The field of objects of supervision is significantly enlarged and confronts the supervisory structures with new quantitative and qualitative tasks. In addition, financial companies that are classified as significant must carry out so called "threat-oriented penetration tests" (see comments on Article 23). Figure 3 summarises the main contents of the draft DORA .

Figure 3: Themes DORA grouped by articles

Governance (Article 4, steering and organisation)

DORA raises the importance of ICT by optimising the alignment of financial firms' business strategies with ICT risk management. Appropriately, the governing bodies of the supervised entities will have to take a decisive and more active role in the governance of ICT risk management. The concept of cyber hygiene is introduced, which is to be enforced by the management bodies. In the final analysis, management is made responsible for managing ICT risks. This is not a new circumstance, because from a supervisory perspective the essence of a financial company is the management of risks, but with ICT risks a type of risk is now exposed.

The management body must be fully informed about ICT risks. Financial companies monitor third-party ICT providers including the associated risk exposure. In addition, the members of the management body must regularly attend specialised training to acquire sufficient knowledge and skills. Likewise, this knowledge must be kept up to date so that ICT risks and their impact on the business activities of the financial company can be understood and assessed. On the board side, DORA will collectively force more STEM expertise. This development will be car-ried over to the supervisory bodies.

ICT-risk management (article 5 to 14)

The requirements for ICT risk management are based on relevant international, national and industry standards, guidelines and recommendations and address specific functions of ICT risk management (identification, protection and prevention, detection, countermeasures, and recovery, learning as well as further development and communication).

These 10 articles cover operational security topics (referred to here as "resilient ICT systems and tools") that minimise the impact of ICT risks, continuously identify causes of ICT risks, take protective and preventive measures, promptly detect abnormal activities, establish business continuity strategies and contingency and recovery plans. Furthermore, these requirements extend to the security and resilience of physical infrastructures and third-party ICT providers to financial firms.

However, some requirements deserve a closer look:

Article 5 Paragraph 4 (ICT Risk Management Framework) requires the application of an "information security governance system", thus requiring the implementation of an ISMS (Information Security Management System). These are already required by the BAIT (Preamble 3) for credit institutions and for capital management companies (Preamble 2 of the KAIT), insurance companies (Preamble 6 of the VAIT) and for payment and e-money institutions (Preamble 3 of the ZAIT). A fully comprehensive ISMS is rarely implemented in practice. DORA will counter this circumstance through the European harmonisation of ICT requirements, which will be conducive to the enforcement of ISMS. The authors postulate that an ISMS will have to be certified for important pro-cesses in the next round of regulation in 3 to 5 years. This development is favoured by the required threat-oriented penetration tests because this increases the requirements for the protection of information and thus the management of protective measures.

Article 5 Paragraph 9 calls for the creation of a "digital resilience strategy" and at the same time sets out requirements for its minimum content. The strategy will have to be equipped with indicators for measuring and monitoring the defined strategic goals. This gives ICT an enormous upgrade compared to previous strategic goals such as business in the business strategy, outsourcing in the outsourcing strategy and risks in the risk strategy. A resilient ICT is now recognised as an equally necessary condition for the business of the financial sector and must be addressed in a separate strategy. In the light of ICT as a determining factor in the financial business, this is a welcome development.

- First, it increases the bureaucratic burden for financial companies as well as BaFin,

- Secondly, under certain conditions, financial companies can outsource a very sensitive 2nd LoD function It remains to be seen how this "fits in" with the prohibition of outsourcing the ISO function for banks (BAIT II point 4.6), capital management companies (KAIT point 29), insurance companies (VAIT II point 4.7) and for payment and e-money institutions (ZAIT II point 4.6) as well as the risk controlling function according to MaRisk AT 4.4.1.

Article 6 (ICT systems, protocols, and instruments) focuses overall on the application of the state of the art and in this respect does not formulate any new requirements. However, the term "technologically stable" (paragraph 1 lit. d) can be seen as vaguely formulated. Considering the explanations in Article 6 interpreted as "observance of sta-ble supply chains", since not only the protection goal of availability, but also the protec-tion goals of authenticity and integrity (in the case of software) are addressed, the regulatory space and the accompanying rational should be described sufficiently pre-cisely.

Article 7 (Identification) requires in detail a structural analysis/process map (paragraph 1), risk management (paragraph 2), risk analyses for each significant change (paragraph 3), knowledge of all resources, partly in directories (paragraph 6), such as accounts, networks, hardware, critical physical equipment, configurations, connections and interdependencies (in paragraph 4) and the processes at ICT third party providers (in paragraph 5). Paragraph 7 requires the periodic assessment of the ICT risk of legacy ICT systems without specifying the term "legacy ICT systems". The requirement to be aware of all resources in paragraphs 4 and 5 should already be fulfilled by financial companies as part of the structural analysis/process map (paragraph 1).

Article 8 (Protection and Prevention) requires monitoring and control of the functioning of ICT systems and tools (in paragraph 1), ensuring resilience, continuity and availability of ICT systems as well as the CIA protection objectives of data in the complete processing chain - storage, use and transmission (in paragraph 2), the use of cryptography (in paragraph 3), an "information security policy" to achieve the CIA protection objectives (in paragraph 4 lit. a), a need-to-know identity access management (in paragraph 4 lit. c), the protection of cryptographic keys (in paragraph 4 lit. d), a change management (in paragraph 4 lit. e) and a strategy for patches and updates. In addition, there is network segmentation and change management for emergencies, including reporting lines. The above-mentioned "Policy for Information Security" addresses the classic management of assets in the context of "information classification" and "information labelling"; this must be supplemented by the protection of information along its life cycle and the applications and systems that process it, ideally through an IT operation manual.

Article 9 (Detection) is dedicated to the detection of anomalies in the performance of ICT networks and ICT incidents. The detection capability must be equipped with adequate resources and capacity. Credit institutions have a special requirement for anomaly detection of trade reports (in paragraph 4).

Article 10 (Countermeasures and Recovery) introduces an "ICT Business Continuity Strategy" in paragraph 1 and details it in the contents in paragraph 2 as a mixture of Incident Management and Business Continuity Management. Paragraph 3 introduces an "ICT Disaster Recovery Plan" which is to be independently audited. What is meant is an ICT plan for the ICT risk management framework from Article 5(1), i.e., the "management of risks" and a "high level of digital operational stability". In plain language, the risk management process must be reviewed at least by the internal audit. The annual audit is also an appropriate audit. The audit of "digital operational stability" can best be realised through one of the big two new topics of DORA: the threat-oriented penetration tests (see comments on Article 23).

Paragraph 4 leads on to business continuity plans. These must be reviewed at least annually, together with the communication plans referred to in paragraph 5. This is followed by the obligations to establish a crisis communication function (paragraph 6), to keep records of incidents (paragraph 7), the requirement specifically for CSDs to report test results to supervisors (paragraph 8) and again for all financial firms to report costs and losses from ICT incidents to the competent authority. In short, financial firms must implement a Business Continuity Management System (BCMS). According to the au-thors, they should approach this with the help of BSI Standard 200-4. A comment on this paragraph as well: What does the competent authority do with the reported costs and losses? This database is a worthwhile target for organised criminality and thus an exposed target for attack.

Article 11 deals with "strategies for data protection and recovery procedures" and imposes specific obligations on central counterparties (paragraph 3) and central securities depositories (paragraph 4) regarding recovery plans and the secondary processing location (paragraph 5).

Article 12 deals with "learning processes and further development" after ICT incidents and in paragraph 2 obliges financial companies to report changes to the competent authorities. However, no criteria for reporting are specified.

Article 13 "Communication" is unsurprising and requires financial companies to have communication plans (paragraph 1) that distinguish between internal and external recipients, with internal being further subdivided into those knowledgeable about ICT risk management and all other persons, and the assignment of at least one person to implement the communication strategy and act as a spokesperson externally.

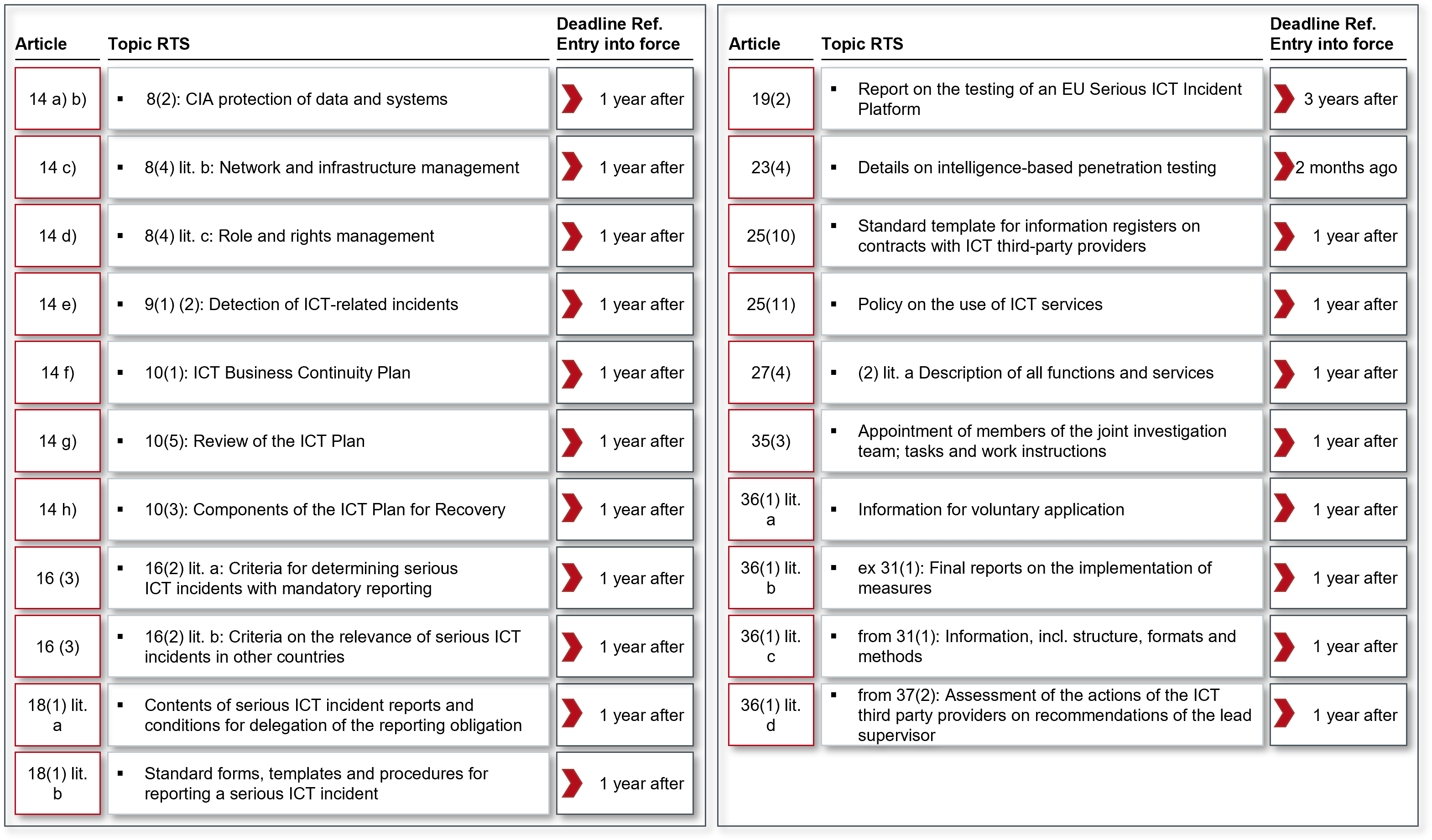

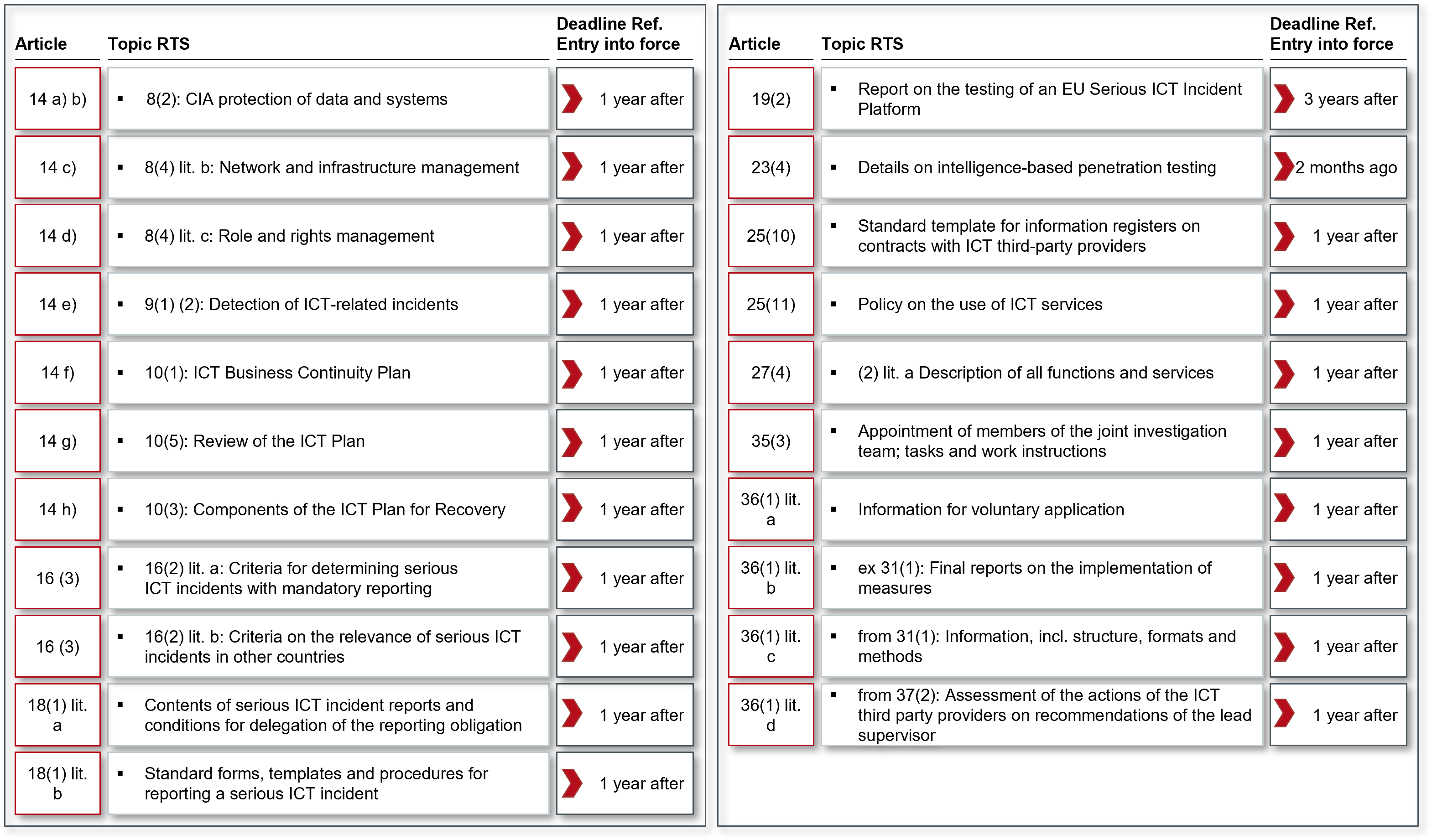

Article 14 (Further harmonisation of tools, methods, processes, and policies for ICT risk management) introduces for the first time "Regulatory Technical Standards" (RTS) to be developed by the ESAs in cooperation with ENISA. These are to further detail the policies, procedures, protocols, instruments, components, tests and elements for ICT security specified in Articles 8, 9 and 10.

A compilation of all RTS to be created from DORA can be found in Figure 4

Figure 4: Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) resulting from DORA

Figure 4: Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) resulting from DORA

Reporting ICT-related incidents (Articles 15 to 20)

The reporting system has been supplemented. The following six articles detail the requirements for reporting ICT incidents

Article 15 imposes on financial companies a "procedure for the management of ICT-related incidents". This must include, among other things, the aspects of integrated monitoring, handling and follow-up of ICT incidents, their tracking, logging, categorisation and classification according to severity and criticality, up to communication plans for internal/external and a reporting system. This topic on the management of security incidents is usually dealt with in an ISMS in the segment of the same name.

Article 16 (Classification of ICT-related incidents) focuses on classification criteria of ICT-related incidents: these are number of affected users, duration, geographical spread, data loss, severity of impact, criticality of affected services and economic impact. Two RTS are also created from this article (see Figure 4).

Article 17 defines, among other things, deadlines for the "reporting of serious ICT-related incidents" to the competent authority (para. 3 lit. a) - subdivided into initial report, interim reports, and final reports. Delegation of reporting obligations is only possible with the approval of the competent authority, which represents a bureaucratic hurdle. The competent authority informs the appropriate ESA authority, in the case of financial companies also the ECB, as well as the so-called "one-stop shop" according to the NIS Directive - in Germany the BSI.

Article 18 (Harmonisation of content and templates of reports) under this Article, ESA , ENISA and ECB shall develop an RTS on the content of serious ICT incident reports and the conditions for delegating the reporting obligations to third parties.

Article 19 (Centralisation of serious ICT incident reporting) sets out the task for ESA, ECB and ENISA to prepare a report to consider the establishment of a single EU platform for serious ICT incident reporting. The report is to be submitted to the European Parliament and the Council 3 years after the entry into force of DORA. German CRI-TIS operators already had difficulties with this centralised reporting platform at the time of the UP KRITIS and the IT-SiG 1.0 in the years 2008 to 2015; it therefore remains to be seen how this project will be taken up at the European level, because this central database represents a highly motivating target for attacks.

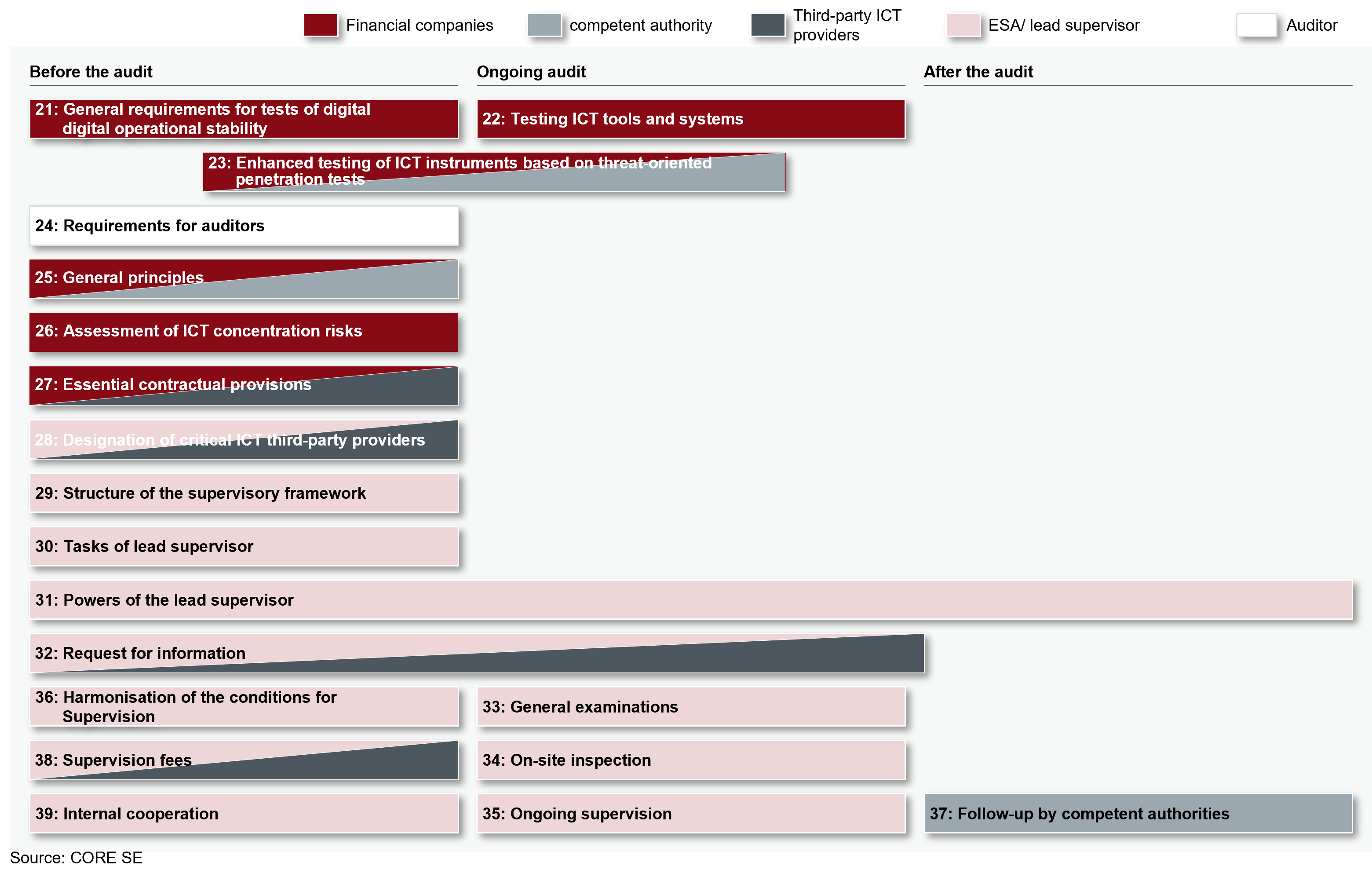

Digital Operational Stability Review - Articles 21-24

Chapter IV (Articles 21 to 24) and Chapter V (Articles 25 to 39) form the audit-relevant articles and they span the framework for the audit of ICT in financial companies in general and ICT third party providers in particular - Figure 5.

Figure 5: Audit-relevant articles for financial companies and ICT third parties

Figure 5: Audit-relevant articles for financial companies and ICT third parties

Chapter IV, with Articles 21 to 24, presents the testing of digital operational stability. New and thus particularly worth mentioning in relation to Article 21 (General requirements for digital stability audits) is the establishment of a program for the annual digital stability audit of all critical ICT systems and applications; this includes content from Articles 22 and 23 and a risk-driven audit of the operational stability including the mitigation of all findings. The description of the scope as "digital operational stability" includes all applications, components, systems, and information and is new in this scope. So far, the regulation reduces the effort through expressions such as "material outsourcing", "critical systems" or even "important systems". Now the financial company must be fully digitally operationally stable.

Article 22 (Testing of ICT instruments and systems) specifies tests to be carried out in accordance with Article 21 and opens up a wide range of requirements for analyses, reviews and assessments. Specifically, CSDs and CCPs must assess the vulnerability of changes to critical functions, applications and infrastructure components.

According to Article 23 (Extended audits of ICT instruments, systems and processes on the basis of threat-oriented penetration tests), critical financial companies (for a definition of which are critical, see Article 23(3)) must carry out threat-oriented penetration tests every three years. These penetration tests shall cover at least critical functions, including outsourced functions, and shall be performed on live production systems. The competent authority shall approve the scope of the penetration test and once performed, shall also certify that it has been properly conducted.

The competent authority shall identify financial companies to perform threat-based penetration testing using the factors set out in paragraph 3. The ESA and the ECB shall jointly establish an RTS for intelligenceled penetration testing on the aspects of

- Scope of threat-based penetration testing

- testing methodology and testing approach, finalisation of the tests, and

- the nature of supervisory cooperation in the case of financial companies operating in several member states.

Obtaining the approval of the planned penetration test from BaFin means further new administrative burdens for financial companies. BaFin will also have to build up further capacities due to the number of new supervisory objects and the large number of extended IT-related requirements.

Another challenge is the requirement to conduct penetration tests in the productive system, as this involves various risks (see box "Risks of penetration tests in a live environment"). Here, the authors advocate penetration tests in staging environments and the justification of comparability to a penetration test in the live environment in the form of a risk analysis.

Article 24 (Requirements for auditors) defines the conditions for threat-based penetration testing examiners. They must be certified by an accreditation body or adhere to formal codes of conduct or ethical frameworks. External auditors must also demonstrate an independent assurance or attestation of reliable risk management, including protection of confidential information, and insurance coverage (professional liability and malpractice/negligence).

It must be clarified which codes of conduct and ethical frameworks meet the requirements and which institution may certify compliance. The same applies to the assurance and the audit certificate. It must be avoided that, in case of doubt, formal criteria with new administrative hurdles take precedence over established trusting business relationships between financial companies and penetration testers.

Managing the risk from ICT third party providers - Articles 25-39

The large Chapter V on ICT third party providers consists of 15 Articles 25 to 39 and is divided into two sections - Section I (Principles for reliable management of risk by ICT third party providers) with Articles 25 to 27 and Section II (Oversight framework for critical ICT third party providers) with Articles 28 to 39 - see Figure 4.

Article 25 (General Principles) sets out the framework for managing risk from ICT third party providers and in paragraph 3 requires the development of a "Strategy for Risk from ICT Third Party Providers" as part of the ICT management framework. This must include, among other things, a register of contracts with ICT third party providers. Furthermore, ICT third party providers must inform the competent authority about the planned awarding of contracts for critical or important functions (also retrospectively when a function is upgraded), which is already required by the FISG in Germany. Among other things, financial companies must assess the increase in ICT concentration risk (see comments on Article 26 below). Paragraph 9 requires comprehensive and documented exit scenarios "where appropriate" as well as their "sufficient" testing. There is a need for clarification here: when must financial firms test exit scenarios and in what form? Is a plan discussion sufficient or must it be a functional test? For clarification, it should be stated that XAIT (BAIT / KAIT / VAIT / ZAIT) does not impose a requirement for the complete test transfer and test commissioning of the entire IT system landscape from one service provider to a second service provider.

Article 26 (Preliminary assessment of ICT concentration risk and further arrangements for further outsourcing) imposes further new assessment and decision-making obligations on financial companies. In determining ICT concentration risk, they must consider whether they use third-party ICT providers that are "not readily substitutable" or enter into "multiple contractual arrangements with the same/closely related third-party ICT provider". In doing so, financial firms must investigate alternatives. They must also assess the risks of outsourcing key functions to subcontractors through third-party ICT providers. This is already known from data protection regulation, but now finds its way into European financial regulation.

Finally, financial companies may only conclude a contract with a third-party ICT provider from a third country if compliance with data protection and effective enforcement of the law are guaran-teed. These requirements stem from the ECJ's Privacy Shield ruling of 16 July 2020 - better known as Schrems II - and suggest that this issue has been resolved for third-party ICT providers in Europe. This is not the case: the processing of personal data in hyperscalers of US origin - in the USA or in Europe as a subsidiary of a US company - is currently not possible in compliance with the GDPR, because for this the European outsourcing company would have to prove that the USA has a level of data protection comparable to that in Europe. The European com-pany is regularly unable to provide this proof.

Article 27 (Essential contractual provisions) describes in detail the minimum contents of the contract between the financial enterprise and the ICT third party provider. Worth mentioning from the draft is a detail from paragraph 2 letter j, according to which the termination rights and the related minimum termination periods must correspond to "the expectations of the competent authorities". For this purpose, these expectations should be known to the financial companies in advance - keyword "IT expert committee". According to paragraph 3, financial companies and third-party ICT providers should use standard contractual clauses, if available. This Article will also give rise to an RTS which, according to paragraph 2(a), will provide a clear and complete description of all functions and services to be provided by the third-party ICT provider. It remains to be seen whether and how the supervision of the ICT third-party providers will affect the willingness of the hyperscalers, for example, to be more responsive to the ideas and wishes of the financial companies. So far, the negotiating power lies with the hyperscalers, despite the mod-eration of regulation.

Central to the DORA is Article 28 with the regulations on the "designation of critical ICT third-party providers". If an ICT third party provider combines a certain amount of assets of financial companies using it, the ESA (and not the national competent authority) provides the "lead supervisor" of the ICT third party provider. In the "Joint Committee" (the cooperation of EBA, EI-OPA and ESA under the ESA to DORA), the ESA shall designate ICT third party providers, considering the criteria set out in paragraph 2. Special mention needs to be made of the "sys-tematic impact on the stability, continuity or quality of the provision of financial services in the event of operational failure of the ICT third party provider". The number of financial companies for which the third-party ICT provider provides services must be taken into account. It must be pointed out here that hyperscalers effectively counter these risks with their technically unlimited scalability and globally distributed availability through "availability zones". The mechanism for-mulated in letters b) and c) of paragraph 2 consisting of "systemically important institutions" (G-SRI) and "other systemically important institutions" (A-SRI) in their use of ICT third-party providers should also be considered in the designation of critical ICT third-party providers. The same applies to the interrelationship among each other and in the rest of the financial sector.

It can be questioned how the ESA will manage this while maintaining a balance between free competition, restrictions on competition and technological overview. Letter d deals with the degree of substitutability of the ICT third-party provider: here, a development would be unfavourable according to which the first financial companies using hyperscalers may continue to use them, but financial companies that want to use hyperscalers later may no longer do so because the market shares of the ICT third-party providers are too high. According to paragraph 8, third-party ICT providers can apply for inclusion in the list of critical third-party ICT providers. This is because non-listed ICT third parties will have a hard time in the market. However, according to paragraph 9, financial companies may not use a third-party ICT provider located in a third country if it would be classified as critical in the European Union. The question here is how financial companies are supposed to know whether this third-country ICT provider has been blacklisted in the Union. To do this, financial companies must be able to simulate this designation by the ESAs, i.e. use a reliable assessment system of the ESA.

Article 29 (Structure of the supervisory framework) contains an interesting detail in the fourth paragraph: The "Supervisory Forum" (a sub-committee of the ESA that carries out preparatory work for individual decisions and joint recommendations for critical ICT third parties) presents comprehensive benchmarks of critical ICT third parties. What does this statement mean in con-crete terms? Does the ESA create a "best-of list" of ICT third parties with the best benchmarks? What would this mean for less performing ICT third parties?

The "tasks of the lead supervisor" in Article 30 hold no surprises in assessing the quality of the ICT third party providers' management of ICT risks as their main task. Paragraph 3 sets out the lead supervisor's requirement to supervise critical ICT third parties through an annually updated plan. The competent authority (in Germany BaFin) may only take measures at the ICT third party provider in consultation with the lead supervisor. This represents a previously non-standardised division of power between national supervisors and the European ESA. Today, BaFin can act autonomously. Article 31 regulates the "powers of the lead supervisor": The lead supervisor can request all necessary information and documents from the third-party ICT provider, conduct investigations, review the mitigation measures taken and make recommendations on all contents of Article 30(2). These "recommendations" are to be understood as conditions and are therefore to be implemented mandatorily. Among other things, the lead supervisor may prohibit the use of a third country ICT third party provider for critical or important functions of the financial companies. The Article will be publicised by the possibility of imposing a periodic penalty payment in case of non-compliance with paragraph 1(a) to (c), i.e. if the third party ICT provider does not cooperate with the investigation. According to paragraph 8, the ESA may publish the periodic penalty payments subject to conditions.

The other three articles detail the lead supervisor's powers under Article 31(1)(a) and (b):

- Article 32 "Requests for information" (referred to in Article 1(a)).

- Article 33 "General investigations" (referred to in Article 1(b) as "investigations")

- Article 34 "On-the-spot checks" (referred to in Article 1(b) as "inspections").

Regarding Article 33, it should be noted that the powers of the lead supervisor read like a police summons, including the handing over of recordings of telephone conversations. Article 35 (Ongoing Supervision) introduces a "joint investigation team". Such a team will be established for each critical ICT third party provider and will consist of a maximum of 10 members drawn from the lead supervisor and the competent authority. All members must have expertise in ICT and operational risk and the team will be coordinated by an ESA staff member. The ESA will develop an RTS on the appointment of the members of the joint investigation team and the tasks and working arrangements of the investigation team. In accordance with paragraph 4, the lead supervisor will make recommendations to the critical ICT third party provider and the competent authorities within 3 months of the conclusion of the investigation. Article 36 aims to "harmonise the conditions for the conduct of supervision" and requires the ESA to draw up various RTSs (see Figure 4).

Article 37 "Follow-up by competent authorities" is the "counterpart" to Articles 30 to 36 and is placed in the timeline after the lead supervisor's review and recommendations. And this is where paragraph 2 presents a "decision contradiction", because financial firms must take into account the risks identified in the lead supervisor's recommendations to critical ICT third parties. Financial companies are not aware of these recommendations because they have not been informed by the lead supervisor or the competent authority, so that asymmetries can arise between the expectations of the competent authority and financial companies regarding third-party ICT providers. In the unlikely event, this could also lead to findings in the case of supervisory objects. Finally, Article 38 informs ICT third parties about the "supervisory fees" they have to pay for supervision by ESA and competent authorities.

Another important side note on deadlines: The two central articles on examinations 23 and 24 will apply 3 years after the entry into force of DORA, i.e., in five years from today's perspective.

Recommendations for financial institutions and supervisors

Both financial companies and supervisors should not wait for DORA to come into force. Even if the final version of the DORA will differ from the present draft, the authors assume that the es-sential contents will not change substantially in quantity or quality. Therefore, both groups of addressees should start preparing for the DORA, even if it comes into force in 2 years for the time being. A situation like that with the GDPR, which since its adoption in May 2016 came into force two years later in May 2018 and "surprised" many market participants, should be avoided. The DORA makes too high demands on technical equipment and organizational skills, on thematurity of the organisation in risk management and information security and on the skills of the responsible persons of all parties involved to wait.

In addition, a distinction must be made between financial companies that are already familiar with DORA requirements from other regulations and financial companies for which DORA represents the first catalogue of requirements for information security. The first group includes all banks, insurance companies and payment service providers, for example, because they have to fulfil requirements such as BAIT, VAIT and ZAIT. Many of the new addressees of DORA will belong to the second group. The recommended preparatory steps are:

1) Set-up, pilot and operate a certifiable ISMS

In the regulated financial sector, an ISMS is already mandatory, but the range of quality of im-plemented ISMS is wide. One of the focal points of management should be directed towards the certifiability of the ISMSs currently in use. In addition, for many of the new DORA supervisory objects, there is currently no obligation to operate an ISMS, so that these financial companies are faced with considerable expenses. If the requirement for a certified ISMS is introduced in the next round of regulation, a certifiable ISMS is the best preparation

2) Focus on DORA rule areas, gap analysis and mitigation of findings

All financial companies should check the conformity of their organisational structure and pro-cesses with the four DORA rule areas:

- requirements for ICT risk management

- reporting of ICT incidents

- audit of digital operational stability

- audit of risk from ICT third party providers

Possible findings by auditors should be eliminated preventively. An ISMS from step 1) provides a solid and equally indispensable basis for this second step.

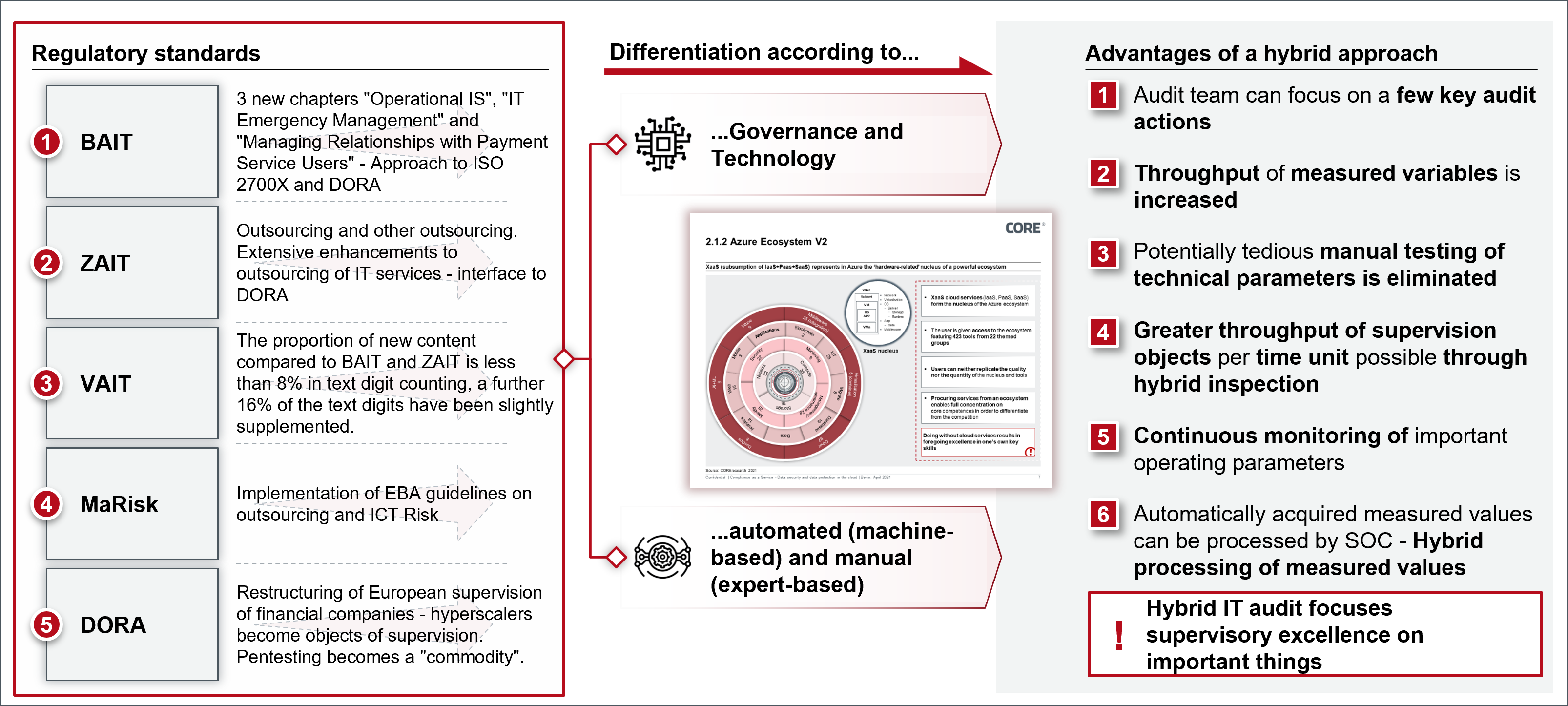

3) Preparation hybrid IT audit

Financial companies and supervisors should jointly develop a standard for a hybrid IT audit. DORA will force further digitalisation steps of a multitude of audit procedures. A hybrid audit approach consisting of automatically recorded variables (machine-based) and manually performed audit procedures (expert-based) offers various advantages (see Figure 5) and reduces efforts for financial companies and supervisors.

Figure 6: Dual hybrid perspective on governance and technology

4) Strengthen supervision

DORA will greatly increase the quantity (number of financial firms) and quality (in-depth knowledge of ICT and risk management) of supervisory tasks, requiring an appropriate response in the form of more staff with STEM skills. The joint development of the hybrid IT auditing standard with financial companies would focus supervision more on essential audit procedures and supervisory content and possibly contribute to a European audit framework.

Fazit

DORA will harmonise numerous existing requirements for the use of modern technologies and the management of risks for the first time through an EU-wide regulation. With this, DORA es-tablishes the first EU-wide application of numerous existing requirements through an EU regulation. This fact justifies the hope for a significant reduction of supervisory and audit administration for financial companies, an acceleration of digitalisation in the financial sector and the further development of STEM skills to equip management as well as supervisory bodies with know-how on ICT organisation and risk management.

The ability of financial companies to counter cyber-attacks with appropriate measures and resilience is expressed in the DORA's thematic priorities and requirements catalogue. These are digital operational stability, auditing and the inclusion of risks through outsourcing to ICT third-party providers in the internal risk inventory of financial companies. Supervised entities would do well to anticipate DORA now and set up a programme to "Fitness DORA" - first steps would be to

- set up and operate a certifiable ISMS,

- gap analysis of the four main topics of DORA

a. Requirements for ICT risk management

b. Reporting of ICT incidents

c. Audit of digital operational stability

d. Audit of risk from ICT third party providers

and

3. preparing for a hybrid IT audit.

Both audiences - financial firms and the supervisory bodies need to strengthen their STEM skills in quantity and quality.

The European harmonisation of the supervisory, audit and sanctions system creates a comparable and thus reliable basis that is recognised by all stakeholders because it is worthy of trust. DORA thus offers the European financial sector enormous opportunities to improve its competi-tiveness and can serve as a model for other sectors in the area of cyber security and resilience.