Blogpost

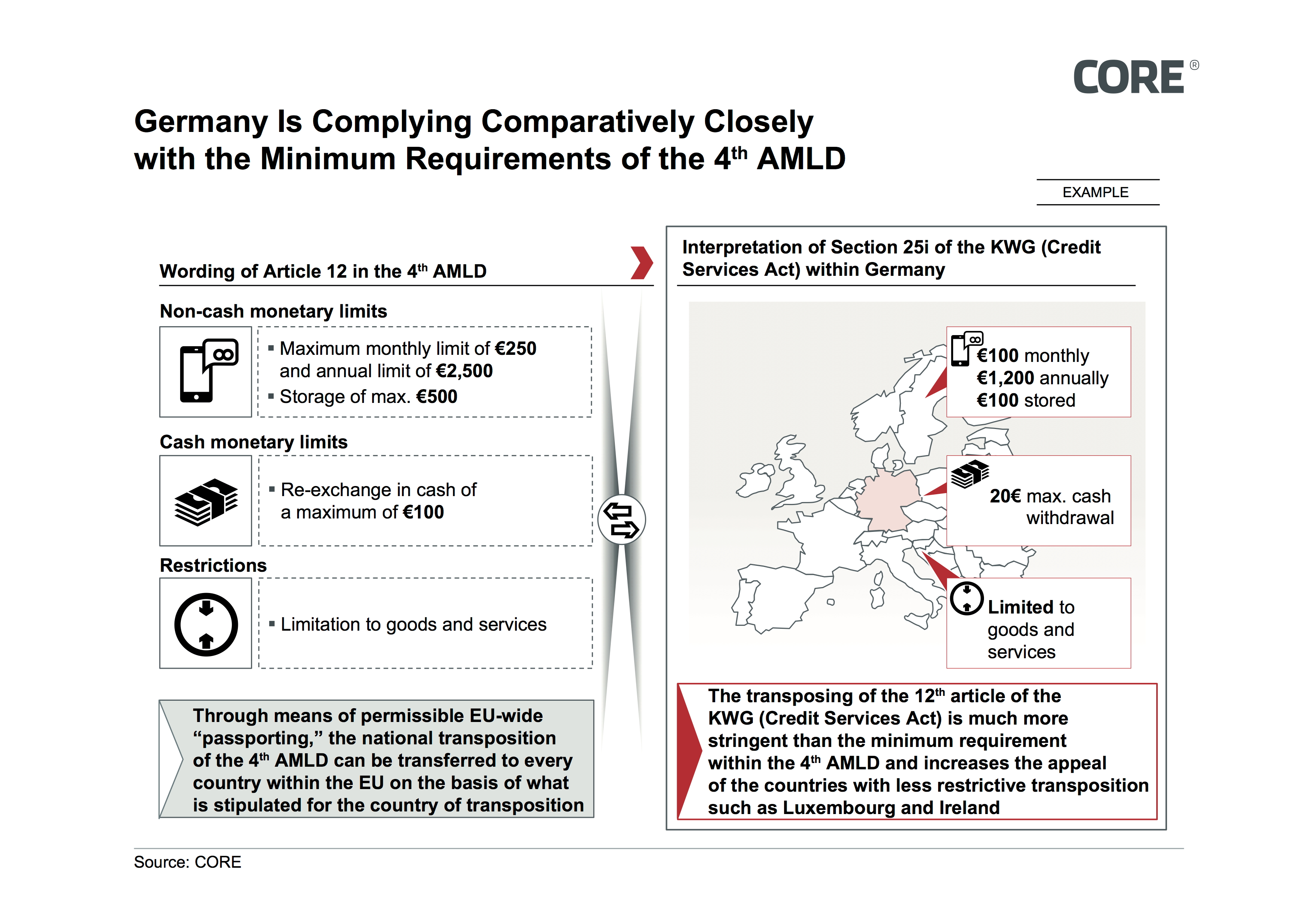

4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive – Provisions of the EU, Germany Remains More Stringent

Meet our authors

Reference items

Expert En - Artur Burgardt

Managing Partner

Artur

Burgardt

Artur Burgardt is Managing Partner at CORE. He focuses, among other things, on the conceptual design and implementation of digital products. His focus is on identity management, innovative payment ...

Read moreArtur Burgardt is Managing Partner at CORE. He focuses, among other things, on the conceptual design and implementation of digital products. His focus is on identity management, innovative payment and banking products, modern technologies / technical standards, architecture conceptualisation and their use in complex heterogeneous system environments.

Read less